Life in the late-1800s, by today’s standards, was dismal for the vast majority of the population.

The average life expectancy at birth was just 45 years.

Most homes had no bathrooms and no one had electricity just yet. There was no such thing as a radio, telephone, motion pictures or professional sports.

Robert Gordon estimates that 87% of all jobs in 1870 could be described as unpleasant based on work conditions.1

More than three-quarters of teenage males aged 16-19 were in the labor force. Today that number is less than 40%. There was basically no such thing as upward mobility as 75% of common laborers were in the same profession a decade later.

A large portion of the labor force was in agriculture. Gordon explains:

In 1870, more than half of men were engaged in farming, either as proprietors or as farm laborers. Their hours were long and hard; they were exposed to heat in the summer and cold in the winter, and the fruits of their labor were at the mercy of droughts, floods, and infestations of insects. Working-class jobs in the city required sixty hours of work per week–ten hours per day, including Saturdays.

The average farm produced an output of $874 in today’s dollars per year. They mostly farmed to survive and provide necessities.

Retirement didn’t exist as most people worked until they dropped dead.

Things began to change in the early-20th century as people moved to cities, technology improved by leaps and bounds and the labor force moved from farming to manufacturing.

The Roaring 1920s ushered in an era where manufacturing exploded because of all the innovation. John Brooks explains in his book Once in Golconda:

Business was in charge of the country to an extent that it had not been since the post-Civil War era of railroad expansion; and its new leader was a newer kind of transportation, the automobile. Just between 1921 and 1923 the annual factory sales of passenger cars rose from under 1.5 million to over 3.6 million, the total number of motor vehicles on the American roads from 10.5 to 15.1 million by the end of the decade the latter figure would account for not quite one-tenth of all manufacturing wages and more than one-tenth of the value of all manufactured goods.

All of those cars required a manufacturing base. The pain from this big move into manufacturing was felt severely by farmers across the country:

Of course, prosperity was not for everyone. The farmer, largely deprived of his huge wartime export trade, ill-equipped by temperament and technology to protect himself against suicide through overproductiveness, and virtually unassisted, in those days, by government, was in the direst of straights. The average price of all farm products was cut in half from 1920 to 1921, and was to regain only a fraction of the loss by 1927; per capita net income for persons on farms fell 62 percent between 1919 and 1921. These catastrophic declines, unprecedented in the country’s agricultural history, meant defaulted mortgages and the failure of the rural banks that held them; in the great years of “prosperity” from 1923 to 1929, banks in the United States were failing steadily at a rate of nearly two per day.

We went from 50% of the labor force working on farms in the late-19th century to less than 2% today. This is progress but it obviously came at a cost to those who had to live through the regime change.

Economic dynamism is one of the biggest strengths of our system. However, one of the biggest downsides to this system is our failure to protect those who are harmed when transitioning from one regime to the next. More on that shortly.

The first significant labor shift for humanity was the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural society. Then we went from farming to manufacturing. The latest shift was a move from a manufacturing-based economy to a service-based economy.

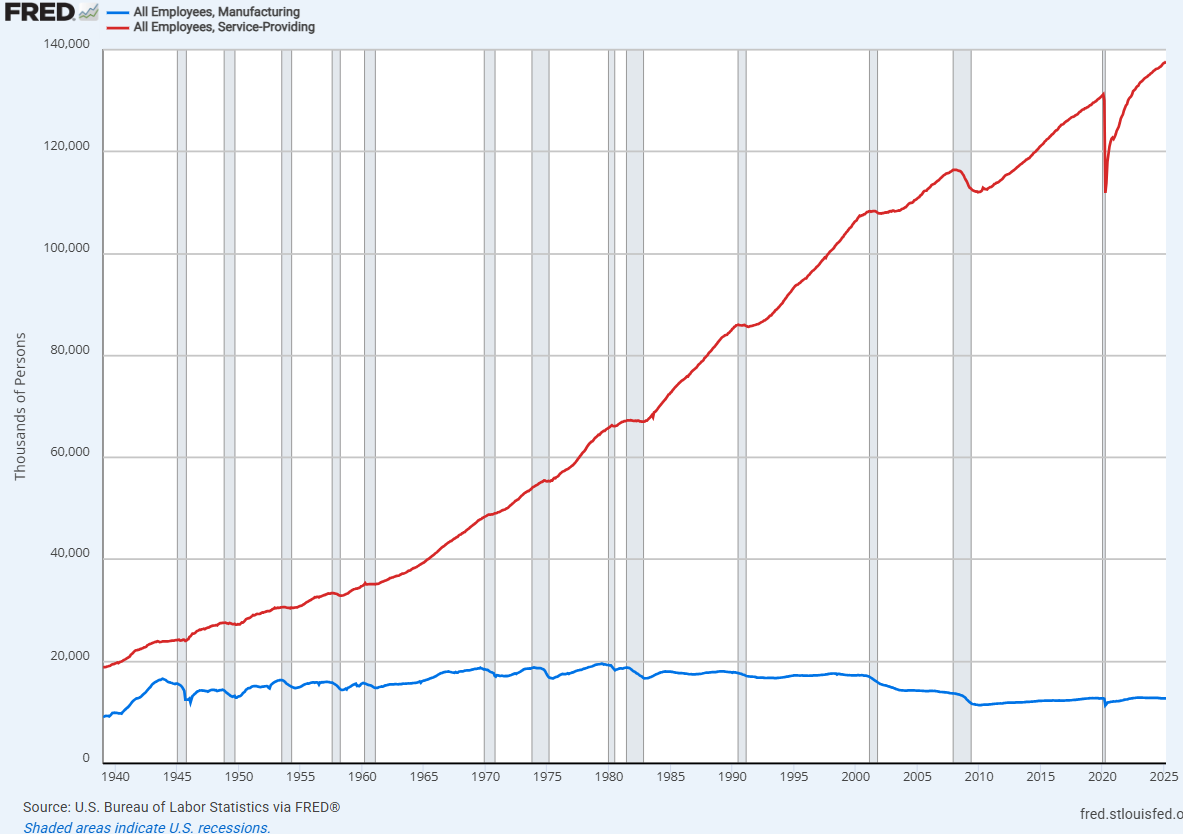

Look at the number of manufacturing employees over time:

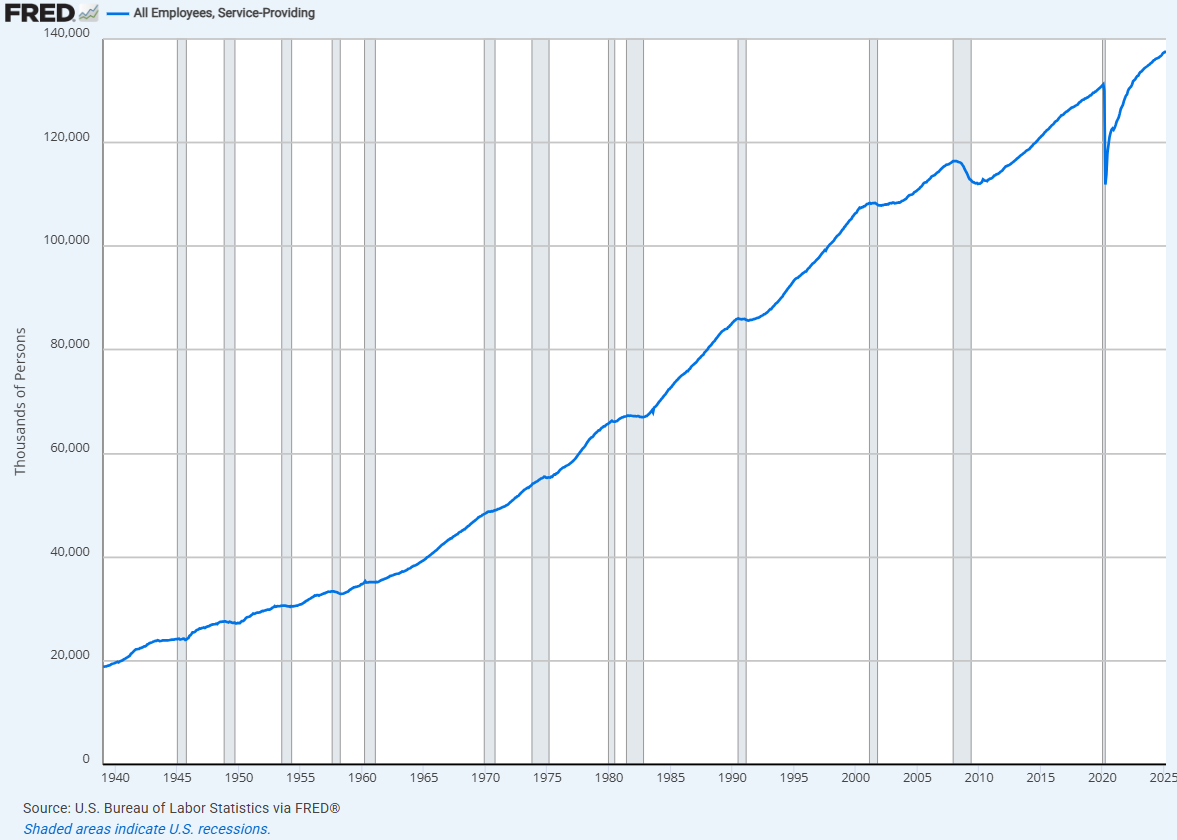

It stagnated and then fell off a cliff. And here is service-based employment:

Now let’s put them together for context:

Right or wrong, we’re never going back to being a manufacturing powerhouse. The shift has been made.

That’s not to say we should abandon manufacturing altogether. The 2020s have underscored the importance of supply chains and the physical world, despite the growing significance of the digital world.

I’m not a fan of the way this trade war is playing out but it proves there are plenty of people who are angry about how disruptive the labor force transition has been on certain industries and towns.

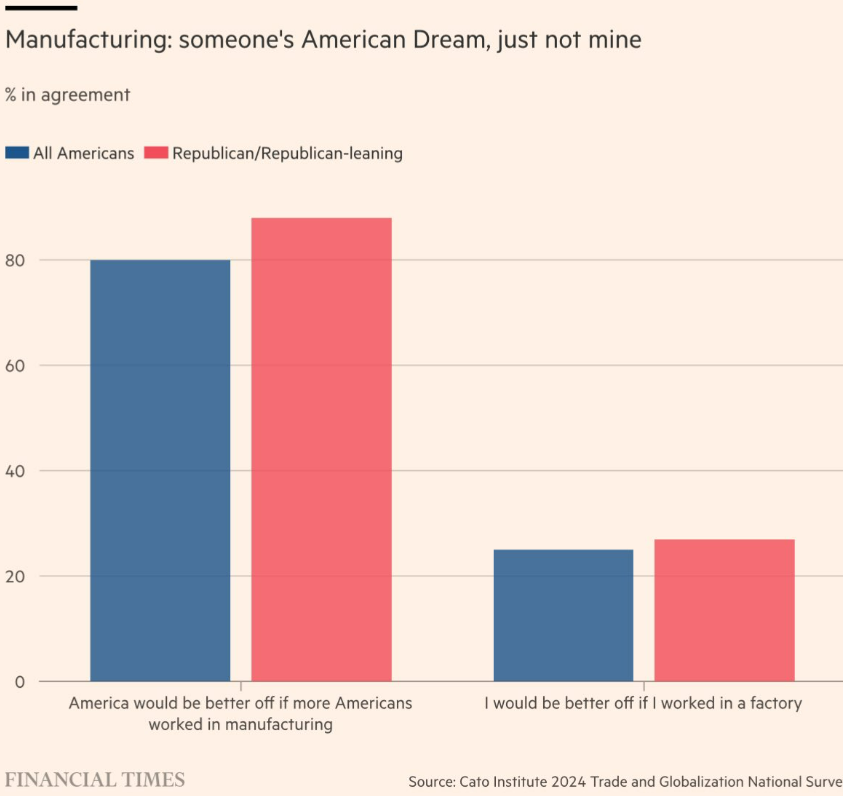

The Financial Times shared the results of a survey about manufacturing employment:

Most Americans would like to see more manufacturing jobs although not nearly as many would like to work in those jobs. It’s also worth noting just 2% of Americans currently work in factories.

They also show how the manufacturing sector has changed substantially this century:

Technology is not slowing down. The combination of AI and robotics will further disrupt the labor force in ways most people can’t even imagine right now.

The good news is that these innovations will also create new jobs.

But it’s worth having a conversation about how to help those who will be displaced in the meantime.

Michael and I spoke about the makeup of the labor market and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Why Are People Miserable at Work?

50 Ways the World is Getting Better

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

Books:

1Today that number is more like 20% although I’m sure some workers would disagree.

Publisher: Source link